Folks Are Talking By Garret Mathews

Introduction

In 1972, I packed my worldly possessions into the trunk of my Ford Pinto and headed to Bluefield, W. Va., for my first newspaper job at the Daily Telegraph. Because I wasn’t very worldly, I only needed half the trunk.

My salary was $90 a week. The only lodging I could afford was a boarding house with no TV, no phone and a shared bathroom. Because the old lady of the manor only charged $45 a month, I managed to stay out of debt.

When I look back over those days, I think of pounding out copy on an ancient Royal typewriter that could have been used as a barbell at a World War II boot camp.

And mailroom guys growing marijuana in the dirt between the cracks of the wood floor.

C.W., their boss, was cool with it and even helped with the harvest.

“Makes ‘em work better,” he told me.

And never completely trusting the contents of the pizza on my desk because pieces of the Depression-era ceiling were always falling down. One night, a staffer thought he was biting into an anchovy and almost needed dental work.

While some graduates of the Daily Telegraph went on to toil at larger newspapers and for The Associated Press, I also worked with a narc, a woman who went to jail for Social Security fraud, a guy who went to jail for assault and a deskman who tried to burn the newspaper building down.

The attempted mass homicide didn’t amount to much. The gothic structure had lived through 80 years of storms, pigeons and angry readers. It could survive a quart of lighter fluid and a boat-load of matches.

My time in Southern West Virginia was life-changing.

I saw a world I had never seen before. One that included coal hand loaders, early United Mine Workers organizers, pool hustlers, bootleggers, mine explosion survivors, snake handlers, flood victims, coal camp baseball players, immigrants from Europe who came to America to work in the coalfields and a female furrier who carved muskrats while eating peanut-butter sandwiches.

While I got some ideas reading weekly newspapers and responding to tips from readers, most of my days were completely unscripted. I drove the back roads and asked around at rural post offices and country stores.

How dumb was I?

My first day in the field was spent in Berwind, a tiny community in the heart of the coalfields. I was told to go up a certain hollow, and I’d find an oldtimer who could tell me about the area’s rich history.

The man had a bad case of black lung from decades of breathing coal dust. It was all he could do to spit two sentences out before gasping for air.

But never mind what he had to say. I was mesmerized by the oxygen tank, the tubes and the mask, and how the fellow had to ration his words to keep from choking.

Sprinting into the newsroom, I gushed about what a great story I had uncovered: A living, (barely) breathing disabled coal miner.

Garret Mathews in 1979 My colleagues broke out laughing.

The story of stories, they said in between guffaws, would have been if I had gone to Berwind and found a miner who wasn’t disabled.

But I stayed with it, and penned more than 2,500 features and columns during my 15 years at the Daily Telegraph.

So why did I make the effort – and it was quite an effort – to sift through my files for the pieces in this online collection?

These men and women are from a bygone era and most are long dead. Their tales help form the fabric of this corner of Appalachia. I want to keep their stories – and memories -- alive for future generations.

It’s also a personal journal of discovery. These accounts are what a young writer found newspaper-worthy during the ‘70s and early ‘80s when the region was only a few years removed from its glory days.

To narrow the time frame for this anthology, I selected stories originally written between 1976 and 1983. While the Daily Telegraph has a healthy circulation in Virginia, I mostly concentrated on the West Virginia side of the border. My main focus was the coalfields – Mercer, McDowell and Wyoming counties.

I love history, so many of the pieces are about men and women who look back on past times. One man was a hobo. One was a silent-screen western buff. One recalled a 1927 train wreck.

Others are included just for fun, like the fellow who built a homemade cannon that fires Double Cola pop bottles.

I don’t want to sugarcoat things. The coalfield counties, especially McDowell, are among the poorest in the state.

Before mines began to mechanize in the early 1950s, McDowell County had close to 100,000 residents. Unemployment was scant, and the family-owned shops and businesses were on solid footing.

The downturn had begun when I arrived in 1972, but there were still plenty of jobs. The coal camp towns were holding their own. Most communities still had their schools and post offices.

Two words best describe the 1980s: Moving van. As demand for coal dropped, dozens of mines either closed or announced massive layoffs. I couldn’t spend a day in the coalfields without seeing a half-dozen U-Haul vehicles, or the like, loaded up and heading out.

I conclude this volume with stories penned in 1983 about the coal slump. There’s one about the plight of a jobless female miner who was raising six children. Another takes a look at the community of Gary in McDowell County that had an estimated unemployment rate of 90 percent. Another piece profiles a doctor in Wyoming County who offered a free clinic to jobless miners who had exhausted their unemployment benefits.

I adore this place, and only wish I could apply a giant Band-Aid to heal the wounds the region has suffered over the last few decades.

The current population of McDowell County is around 22,000. Only about one in three adults is in the labor force. Drug use soars as the hopeless comfort themselves with pills and syringes.

There is no four-lane highway. No chain sit-down restaurants. No decent parks.

It’s almost impossible to attract professional people to the area, especially physicians and teachers. Hundreds of houses are falling down, their absentee owners long gone.

The little towns struggle to keep their charters. The tax base is mostly retired and disabled miners. For young people, leaving the area is almost a foregone conclusion.

Bluefield remains the region’s largest city, but it’s on the same downhill slide. More than 20,000 people lived here in 1960. The population today is less than 11,000.

Downtown is one empty building after another. School enrollment is tumbling. There is precious little new construction.

The present is dim, the future grim.

So I ballyhoo the past with anecdotal accounts from gritty men and women who lived to tell about it.

I’m alerting public and school libraries in Southern West Virginia and southwest Virginia to this site. I’m also putting the word out to regional historians as well as to colleges and universities that offer Appalachian studies.

Time, I hope, is my friend. Before I’m done, I’ll pitch this project to anyone with even a remote interest in the subject matter.

I’m certainly no expert on life in these mountains. Hey, the last sociology class I took was in high school. But I was boots on the ground. I didn’t observe these men and women from afar. I looked them in the eyes.

That, I believe, makes this collection worthy of your consideration.

I hope you enjoy “Folks Are Talking – 1976-1983.”

Garret Mathews -- Jan. 5, 2016

The Silent (Screen) Type

1979

PEEL CHESTNUT MOUNTAIN, W. Va. – At first glance, the white-haired man looks nothing like a collector of old movie relics.

He sucks constantly on a corn cob patch that’s straight out of Dogpatch, and the floppy hat and overalls makes him look like a fellow quite content to sit around the wood stove all day long, making no decision more substantial than choosing snuff or Red Man for an afternoon companion.

But the 69-year-old retired coal miner is a prodigious saver from way back, and don’t be fooled by the drawl that forces a visitor to conduct veritable vigils between words.

Oh, Edgar Shew still keeps the black powder squibs and the metal prongs he used back in the 1930s to blast coal from the then-bountiful Pocahontas mine.

And he has a goodly collection of dusty license plates, vintage six-shooters and Georgia Moon corn liquor bottles.

But just kid’s stuff, Shew says, when compared to the treasure he keeps in a spare bedroom of the white frame house he’s called home since 1925.

The generally toothless man may have the largest collection of cowboy movie posters from the silent-screen days of anyone on the planet.

He figures he has more than 350 paper and cardboard posters promoting the films of Tom Mix, the Hoxie Brothers, Fred Thomson, William Boyd and Buck Jones along with many other ride-‘em-cowboy types whose careers flourished from around 1915 until 1928 when the dastardly talkies came out.

“Haven’t been any decent pictures made since the start of the Depression. I reckon that’s why I haven’t been to the movie show in 50 years.”

Yes, Edgar Shew is a purist – cowboy silent films or nothing.

“To me, no other kind of movie has any plot to it.”

The full-color posters are in amazingly good condition. Only a few are torn, and most could be used by a movie promoter today if he wanted to turn back the clock.

Shew knows of some individual cowboy posters that collectors have bought for upwards of $150.

“But I can’t see me selling any of my collection, though,” he says, grinning, “Because then I wouldn’t be able to look at ‘em.”

He has laboriously researched every silent-screen western ever made, and tells anyone who will listen about the actors, plots, the film studios and even where the movies were filmed.

The highlight of Shew’s roomful of lore is memorabilia relating to the career of Tom Mix.

Edgar Shew holds one of his silent-screen posters

“He was the greatest,” he says of the man who gave us “Riders of the Purple Sage” as well as many other classics. “People can talk about John Wayne all they want to, but for my money Mix was better.”

Shew was injured underground in 1952 – about the time mine mechanization entered the picture, a happening that spelled the end for pick-and-shovel men. He quit three years later and began pursuing his hobby in earnest.

“I only wish I could have been one of those cowboy actors. Of course, in the ‘20s I was too busy digging coal to think about doing much else. I never got to see Tom Mix or Hoxie or Boyd or any of ‘em in person.”

But Shew saw his favorites dozens of times inside the many theaters like the Palace in Pocahontas that dotted the Bluefield-area coalfields in those days.

“I got most of my posters from outside the old movie houses and sometimes, I’m ashamed to admit, I swiped the posters before the particular picture left town. Most of the theater managers were pretty nice about it, though.”

If Shew spotted an old poster, no risk was too great.

Take the time in 1927 when he was riding the train from work back to Pocahontas.

“Trains were real slow in those days, about 10 miles per hour or so. Anyways, when I was riding the rails one day I spied me a cardboard poster of Tom Mix on a telephone pole by the track.

“Now you didn’t see cardboard movie posters much in those days, so I got real interested in grabbing a-hold of that rascal. We got a little closer and I decided it was then or never, so I jumped off the train and pulled the poster from the pole. I ran like a wild man, and a mile or so later I caught up with the train and finished my trip.”

Shew has only one problem when it comes to his cowboy collection. That would be his inoperative movie projector.

“Years ago, this salve company would give you a hand-crank projector if you turned in enough of their coupons. Well, I turned in a passel of coupons, and that old projector did me real good for a long time until recently when the motor gave out. I haven’t gotten around to getting a new one yet.”

Edgar Shew likes to concentrate on a narrow field of endeavor. Just silent-screen westerns. No vehicle. No wife.

“I ran after the women for a spell and then I thought better of it. I don’t have any regrets about that or anything else except when the fools took all the saloons out of the coal towns.

He lights his pipe for the umpteenth time as he looks at the smiling poster of Tom Mix.

“Times were true back in those days,” he says as a frown displaces his normally glad countenance. “Even the bad guys were good guys in their own way.”

Fifty Tons A Day And Then Some

1977

KIMBALL, W. Va. – The words come out in broken English and, with no front teeth as a barrier, they’re on top of you before you know it.

“I just liked to work. Once I’d start, I’d rarely stop. One day back during the Second War I loaded 53 tons by myself.”

Tom Battlo wheezes with black lung now, but in the days when coal was hand-dug and hand-heaved, the man had few equals.

These days he lives above the Beauty Bar, an enterprise operated by one of his daughters. He watches television a lot, a nod to his diminishing health.

“I always worked by myself,” Battlo recalls. “I would always get out of it when they would want me to have a buddy. I would put up my own timbers, do my own blasting and shovel my own coal.”

He worked at McDowell County operations in Roderfield, Premier and Keystone for more than 40 years beginning in 1913. He came to America from Italy in 1910, and spent three years in New York City with tens of thousands of other immigrants before hearing of work in West Virginia.

Battlo remembers loading coal for 65 and, later, 75 cents per six-ton buggy. Each car had his tag on the side, and his production was totaled at the end of the shift.

Old hand loaders in the county remember Tom Battlo best for his domination of the $20 war bond prize given every payday during World War 11. The mine operator offered the reward to the man who loaded the most coal. Battlo figures he collected close to $2,000 beyond his normal take.

“I guess some of the boys didn’t like me winning all the time. The super would put my picture up on the bulletin board, and it would usually be ripped down after two or three shifts would turn.”

Battlo says he rarely worked more than eight or nine hours a day.

“I could make all the money I needed in less time. Besides, the rock dust was pretty bad.”

Daughter Jean remembers the child-like excitement of opening her father’s lunch bucket at the end of the day, and having almost all its three-compartment goodies to herself. Her dad rarely took time off to eat.

Times have changed in the coalfields. Hand-loading operations have almost disappeared. Machines do most of the work.

“It’s progress, I reckon,” Battlo says, “but it would take four men today to do the work of one old-timer.”

Tom Battlo started digging coal with a No. 2 shovel. In the late 1940s, he was issued a No. 5, a scoop that holds some 75 pounds of coal.

He was proud of that shovel.

“They didn’t give many men a 5, you know.”

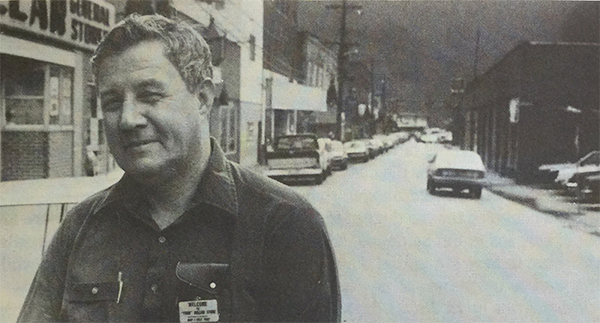

The World’s Greatest 9-Ball Player?

1978

MULLENS, W. Va. – “Hello, boys.”

Buford (Bud) Hypes walks into the Sportsman, a poolroom he owns in this Wyoming County town, and takes his cue out of its fancy carrying case.

“Writer here wants to see me shoot,” Hypes says, pointing my way.

It’s a lucky day for the half dozen or so men in the place. Hypes doesn’t put his talent on display very often.

“Boys, ain’t no mortal gonna rob me at 9-ball,” the 58-year-old man says as he racks the balls. “But you knew that already, didn’t you?”

Somebody asks if an immortal could beat him.

“Hell, I’d rob those kind, too.”

Hypes bills himself as the country’s greatest 9-ball hustler.

“Have been since I was 16,” Hypes says as he makes one shot after another, pausing only instants in between. “I’d go to a town and ask who the best pool shooter was. If he wasn’t around, I’d wait on him. I’d rob the poor man and then go on to the next town.”

While the balding man with the bulldog face says his skills haven’t diminished, his restaurant and property holdings take up most of his time. Hypes and Henry Ball run Bud & Henry’s Grill. Hypes also owns the pool hall, a parking lot and some apartment houses on the same block.

“It’s just like winning at 9-ball. Why not own it all?”

He sometimes goes three or four months without picking up a cue.

“I’ve got me a little peephole at the Grill, though, and if I see somebody burning up the table, I might take a break from washing dishes to come over and rob the boy.”

Hypes says he’s a good businessman. So good that he passes up the $50,000 he says he could earn if he hustled year-‘round.

He used to play exhibition matches at VA hospitals. He and a set-up man would demonstrate trick shots and Hypes learned how to be a showman. He made shots both left- and right-handed and the crowds loved it.

I bring up a familiar name.

“Minnesota Fats? Man, he’s just an old boy named Rudolph. He was working for Brunswick and I never could get him to play me much. But when I did, I robbed him in 9-ball.”

Hypes generally passed up official championships, preferring to play the winner in a big-stakes game after the crowd left.

“The rules of 9-ball are frequently changed during coat-and-tie competitions to keep the audiences interested. They try to make it harder and harder on the good shotmaker. Sometimes they rig things until a lucky man will do as well as me.”

The master has shooting pool down to a fine science. Not even the weather escapes his scrutiny.

“If I’m playing on a cold day like today, I know the rails will be fast and the felt slow. You’d better adjust your game or you’ll lose.”

Hypes says he once ran 379 balls in a row in games of straight pool. A few years ago, he ran 13 racks in a row playing 9-ball.

The man with beef stew on his apron says there’s a schoolteacher in Williamson, W. Va., who’s been particularly benevolent to him.

“One time there was me and these two Class B players hanging around this pool hall where this teacher always showed up after school. Well, I spotted him first and he was heading for the bank. Now I didn’t want this good teacher to put all that good money away so I ran – only time I ever did that – up to him and talked him into a game. I robbed him good and those two Class B boys were pretty mad at me.”

Hypes finds he has to travel nowadays to find a good money game.

“Can’t get any action in Mullens or anywhere else in coal country. They know better.”

He says players have changed over the years.

“A lot of boys today are thugs and they get filled up with dope when they play. Don’t matter much to me, though. I’ll still rob them.”

As Bud Hypes leaves the room, a young boy looks up at him in awe.

“Hello, sonny,” Hypes says, shaking the little hand. “Now you can say you’ve seen the best.”

Bud Hypes at his place of business

Bud Hypes at his place of business

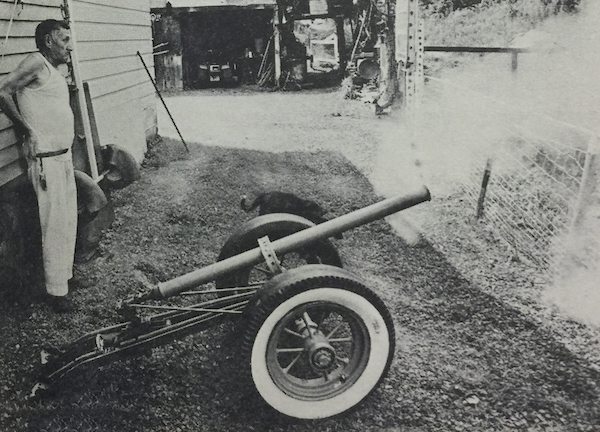

‘Shootin’est Thing I’ve Ever Seen’

1978

BANDY, Va. – John Stout is the proud owner of a 1901 grist mill motor that he says a man just can’t find any more.

The retired coal miner also maintains a dual-purpose chicken coop. Stout’s Cackle Inn, as he calls it, is also a recording studio.

“This boy of mine can write a gospel song in less than 15 minutes, and one of these days we’re gonna lock ourselves in this coop and not come out until we have a tape full of music.”

The Tazewell County man leads the way to the main attraction of his back yard.

A homemade cannon.

“Shootin’est thing I’ve ever seen.”

Stout used the driveshaft from a 1951 Buick for the barrel and “just plain common sense” to finish the rest of the weapon. He added two whitewall tires to the carrier red wagon for class.

He points to a large hill across the road.

“I can lob an old Pocahontas Fuel Company pop bottle over that ridge just as pretty as you please. Why, if I had enough gunpowder behind it, I could fire a round a mile, I reckon.”

Stout uses Pocahontas pop bottles because they fit perfectly inside the innards of his cannon and because he has so many of them.

A common target in recent months has been a sycamore tree about 400 yards from his house.

“Don’t see very many leaves on it, do you? A cannon will do that to a tree.”

Once he blew a mulberry bush to smithereens, and told his wife the damage came from a windstorm so she wouldn’t get mad at him.

“Mother always thinks I shouldn’t aim between the power lines, but she should know by now that I’m an expert with this thing.”

Stout recalls the time an inebriated relative shot off a half pound of gunpowder by accident and almost blew man and machine to the next county.

“That was a fun time,” he says.

True to his promise of giving a demonstration, John Stout turns the cannon toward nearby Columbus Hill and sets off a round. The pop bottle flies through the air like a missile.

“It’s been about 12 years since I’ve built a cannon. All that mine dust in my lungs keeps me from working at anything more than a few minutes at a time.”

He talks about the time he defended his cannon to a curious judge who drove to Bandy to see what was causing all the commotion.

“Told the man it was kinda like a kid’s toy, only bigger. He must’ve liked what I said because he just rode away.”

John Stout and his back yard cannon

John Stout and his back yard cannon

His Work Space Has A 30-Inch Ceiling

1977

CRANE CREEK, W. Va. – Leonard Bailey toils at a small mine that has a 30-inch top and a layer of mud that covers his boots. His days are spent in a deep crouch as he gouges at the coal.

And he likes it.

“It may sound hard to believe, but this operation (Crane Creek No. 11 at the junction of Mercer and McDowell counties) is safer than the ones with so much of a roof that a man can walk upright,” Bailey says as he pours a cup of coffee in the operations room. “Just the other day I was pinned by a big rock, but I shook it off because the thing didn’t drop too far. If that boulder had fallen on me from, say five feet, I’d have been a goner.”

The records prove his point. On the wall are plaques signifying years of accident-free work.

Bailey, a veteran of 33 years underground, has been here since 1966. He’s one of eight men who work at the face some 500 feet from the portal.

“You’ve got a few swag areas where the crew can sit comfortably to eat meals, but most of the mine is just a tad above the loading machine and that’s 28 inches.”

The veteran miner believes it’s easier on the body to work in low coal.

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a back injury at No. 11. Now there are people who get banged-up knees from crawling around all day, but that’s about it.”

Section chief Joe Berry joins Bailey in the operations room.

“A lot of guys go down the road to No. 6 (also a Consolidation Coal operation), but many of them end up coming back here.

“I think a feeling of loyalty builds up among the men when they all share in the hardship of the less-than-wonderful working conditions,” Berry goes on.

Bailey believes the goop at No. 11 is worse to work in than the low ceiling.

“A lot of times, there’s a foot or more of water and that makes it difficult to operate the equipment. Sometimes when you feel that first wave of cold water going down your boots, it makes you think twice about what you’re doing here. Also, it slows production.”

An average of around 500 tons is mined per shift at No. 11. The company gives prizes if a shift can maintain that mark over a month’s time.

While Bailey says that target isn’t “all that difficult” to maintain, he admits the crew doesn’t get the tonnage they would if the top was higher.

“They’ve already mined out the high coal where we’re working,” Bailey explains. “The low stuff is all that’s left.”

How does it feel to stretch out after eight hours spent scurrying around like a gopher?

“So good I don’t have the words for it,” Leonard Bailey says, smiling.

Hoover Times Brought Him To West Virginia

1979

ASHLAND, W. Va. – Ralph Rameriez says if he could write well enough, his life story would make a good book.

The introduction would draw from his days as a member of a wheelbarrow crew at a silver mine in his native Mexico.

And the small man who has never weighed more than 130 pounds would give ample mention to his 33 years in McDowell County mines, and the time he proudly held the record for hand-loading coal.

And there would be at least a chapter or two on Annie, his Polish-born wife, who wears her shawl tucked in a bow under her chin to ward off the winter chill.

“I’m old-fashioned,” she says.

Her 82-year-old husband talks in a staccato voice and uses wildly-waving hands as exclamation points.

“I’ve had it pretty rough…a lot of stories,” he says. “If only I could write good enough. But I don’t.”

Rameriez left Mexico in 1920, figuring life had to be better across the border. He never formally learned English, but hoped his willingness to work hard would overcome the language barrier.

He picked cotton for a few months, and then labored at a sugar beet factory.

“Those were Hoover times and times were bad. There was no work at the factory and no work any place else. Then I heard coal miners were getting jobs. So I got myself to West Virginia in 1925 and I’ve been here ever since.”

He found his way to a boarding house where he met a young woman from Poland, whose husband had gone to Chicago, leaving her and the children to pay the rent as best they could.

Rameriez met the lady, liked her, and when news arrived of her husband’s death in Illinois, the two were married.

“I could load coal as good or better than any big fellow,” Rameriez says. “I did 25 tons or more every day for year after year. I never sat down on the job like some other men and I was never sick. They kept the totals on the office. My name was on the top.”

He was seriously injured in a slate fall accident in 1934 that resulted in spinal damage and a long stint in a body cast.

“I couldn’t even sit at the dinner table with the rest of the family.”

The No. 6 mine at Ashland petered out in 1958. Rameriez did odd jobs on the outside for five more years, but he had loaded his last coal car.

“Silver was no good. Coal work is better. I made enough to educate my children and grandchildren, and I was able to have a piece of land.”

He has a knack for growing things, particularly pumpkins and tomatoes.

“I haven’t been healthy for a long time – my heart, eyes and ears mostly. Anyway, when I go to the doctor I always give him vegetables. I think that’s why we get along so good.”

He pulls out a faded picture of a fashionably dressed young man.

“This is what I looked like when I came to McDowell County. I didn’t have any money, but I wasn’t looking like a tramp for anybody.”

The Ashland coal camp housed several ethnic groups in the heyday of the mining company when the grounds held a bowling alley and a movie theater. Annie Rameriez felt at home with her Polish friends, and Ralph had several Spanish-speaking neighbors who moved to the coalfields for the same reason he did.

No more.

Annie reckons she’s the only one in the camp who understands Polish. Ralph knows he’s the only man left of Mexican descent.

“We have each other,” Annie Rameriez likes to say as nervous fingers work the bow under her chin.

“She and I, we’ve tried to be good people to the Americans,” Ralph Rameriez says. “I know I’ve worked hard enough.”

Mine Is Gone, But Not Bill Byrge

1976

KILLARNEY, W. Va. – The mine is gone, the post office is a memory and the 20 or so remaining families must look at massive slate dumps for a reminder of what used to be.

The Raleigh County community is off most road maps now. Folks get their mail in nearby Rhodell, and except for a scrawled sign pointing the way to the Killarney Freewill Baptist Church, travelers could easily miss the place altogether.

Bill Byrge is one who stayed.

“I call myself a refugee. I spent 46 years in the mines, but retirement comes hard. If I sit on this porch all day, I’ll be gone in less than a month.”

So he sells stuff out of his van and off the porch – tape players, cameras, toasters. You name it.

“This right here is the only enterprise going in Killarney these days. If I don’t got it, I can sure get it.”

Byrge came to Killarney in 1940 from Hazard, Ky. In those days, the community had a population of about 500 and area mines were going full tilt.

“I left Hazard because it was too rough. It seemed like there was a killing a day down there. It was a little better here. There were a lot of fights around Rhodell, but not near as much dying.”

The smile gets wider.

“I was right in the middle of it. Liked to drink, too, but I was smart enough to stay out of the bars. I put down enough to flood that creek over there, but almost all of it was done on this porch here on Saturday nights. I wouldn‘t feel good until after two hours of sweat on Monday.”

The white-haired man learned to brawl at an early age.

“Got hired to be a boxer for this carnival. Monday through Friday, they paid me 10 bucks a day to lose most of the fights. The contract wasn’t there on Saturday, and that’s when I got even with a lot of guys.”

The origin of the community’s name, Byrge says, “has nothing to do with Ireland or across the sea or anything like that. Old-timers told me about this real tough guy named Arney who terrorized the citizens back in the early 1900s. The place got called what it did one night after a bunch of riled people came to his house and started shouting, ‘Kill Arney.’ ”

Byrge was superintendent at the Killarney mine until it closed in 1958. He says there’s still coal in the mine that’s just down the hollow from his porch.

“They only quit because of the low prices they were getting. A few years ago, this coal company approached me about resuming the operation. I said I would get the coal out for $5 a ton. They didn’t like my price and that was the end of that.”

We watch a man in a pickup truck try to get to the top of one of the slate dumps. The driver doesn’t admit defeat until plumes of smoke engulf his vehicle.

“Town might be dying out,” Byrge says, “but that don’t mean we don’t got entertainment.”

Flood Baby Brings Some Needed Joy

1978

BARTLEY, W. Va. – Floodwaters ran high in this corner of Appalachia in early April of 1977. Damage figures soared into the millions of dollars as folks watched cars, refrigerators, furniture and other pieces of their lives go bobbing down bloated rivers like so many leaves in a stream.

I spent the week of April 4-8 doing flood stories, concentrating on McDowell County. The days were long as there were lots of hard times tales to tell.

But there was at least one heartwarming story.

It was near the end of my third day on the road. My little Chevy Monza almost became a flood casualty the previous afternoon, so the Daily Telegraph arranged for a Bluefield Rescue Squad vehicle and a driver to negotiate the inundated roads. Joining us was Frank Jarrell, another Telegraph reporter.

We made one last stop in War when 18-year-old Andy Bruch, our wheelman, monitored an emergency call – something about a woman about to give birth who had no transportation to the hospital.

We lit out for Bartley, about 10 miles away, where we encountered a sobbing woman and her tiny husband. Hysteria was setting in as the woman was afraid she

wouldn’t make it to the Welch hospital a half hour away. She leaned against her tiny husband for balance.

Andy calmed the woman by telling her he had delivered a baby once and there was nothing to it.

We got to the top of Coalwood Mountain. Only 15 more minutes to go.

The sobbing turned to screams. It was time for Brenda Mullens to have her baby. Andy parked the Rescue Squad and climbed in the back of the truck. Frank and I directed traffic.

After a few minutes, I realized I might never have the opportunity to witness a birth up close. I had always heard people say there was a lot of joy and happiness surrounding such an event, so I decided to peek in and see for myself.

I couldn’t have picked a more graphic time. I saw the baby coming out and the corresponding mess in the back. Scampering back to my post, I vowed I would never have children.

In a few minutes, Frank hollered that the birth had been completed and the new little girl was doing find. Then Andy said we still needed to go to the hospital because he didn’t want to cut the umbilical cord.

Frank drove. I operated the yelp and squelch buttons. Andy comforted Brenda and her husband, Mackie, and the newest addition to their family, Angel Marie.

At the emergency room, the doctors complimented Andy for his grace under pressure. I hounded them until they said I did a good job of yelping and squelching.

Three months later, I did a follow-up story.

The Mullens family was living in a HUD (Housing and Urban Development) flood trailer outside Iaeger. They lost almost all their possessions in the flood, and the government trailer was their third resting place since the waters rose that night in Bartley Hollow. They joined 100 or so other displaced families at the hastily prepared trailer park. Mackie, a coal miner, was still unemployed.

Despite temperatures of more than 90 degrees inside the trailer, Angel Marie was smiling and cooing.

“She only cries when it gets too hot for her to bear and that’s not often,” Brenda says. “She can stand the heat better than I can.”

The mother of two looked back over April 7.

“I was in my tenth month and I started having labor pains around 11 o’clock that morning. The pain stayed for a while and then it went away. Mackie went down the hollow to help some neighbors clean up after the flood.

“About three hours later, the pain hit again. I knew I had to go to the hospital fast so I bathed Louis (her first-born) and got him all squared away. Then I walked down the road and caught what I thought would be a ride to the Welch hospital.

“But the car broke down and me and Mackie called the Big Creek Rescue Squad.”

That’s when we entered the picture. Our Bluefield unit was idling next to the War Police Department, and Andy picked up the distress call.

“I was afraid for my baby,” Brenda Mullens recalled. “It was really bumpy in the back of that ambulance.”

She brought Angel Marie into the living room.

“They let her stay with me in the bassinet that night. There were no complications and we went home three days later.”

Brenda and Mackie Mullens weren’t happy at the crowded trailer park. They hoped to move to Bradshaw to be closer to friends and family.

“But we’ll make it. Angel Marie’s gonna be our good luck charm.”

Brenda and Angel Marie Mullens

Brenda and Angel Marie Mullens

‘I Am Not Of This World, But The Next’

1979

JOLO, W. Va. - The rattlesnake winds itself around the handler’s arm and becomes like a giant bracelet.

“Jesus, yea Jesus. Praise the Lord.”

The others on the rostrum chant as the holder raises his free hand to the ceiling.

“Jesus…Jesus…Jesus.”

More rattlesnakes are brought out of the big brown box. The music from the electric guitars quiets and the dancing stops as the sweating saints of the church hold the reptiles at arms’ length. The snakes’ heads shimmy up and down slowly as if mesmerized by the religious spirit that permeates the small room.

“A lot of people read Mark 16 in the Bible and kinda skip over the serpent part,” the Rev. Bob Elkins tells his flock. “Well, you can’t skip over it. You got to believe the whole thing.”

The service at the Church of the Lord Jesus is informal and non-regimented. There are no hymnals or prayer books. No specific time is budgeted for preaching or singing. Carefree children chew gum and play with pocketbooks.

“There are those who think this is show,” thunders Dewey Chafin, who holds a giant wad of rattlesnakes. “Let those who think thusly reach into the serpent box.”

There are no takers from the crowd of 50 or so in the congregation.

“One night, this serpent must’ve latched on to my thumb for a good minute,” says Chafin after the service. “I can’t describe the pain. All I can say is a toothache ain’t nothing compared to it. All together, I’ve been fanged way more than 60 times.”

There’s never any pressure on those in the back rows to handle the snakes, most of which are caught in these same mountains.

Women members of the Church of the Lord Jesus do not wear pants or jewelry and are not permitted to cut their hair. Men are required to dress conservatively. Drinking and smoking are taboo, as is going to movies or ball games.

Believers usually don’t seek medical attention when bitten.

“Trusting in the Lord and living a good life are real important,” the Rev. Elkins continues. “I could never put my hand into the snake box if I had any guilt feelings at all.”

Tim McCoy was bitten on the fingers and almost died.

“You never know what those bites will do to you,” the McDowell County man says following the three-hour service. “When I was bit, I missed a lot of work at the Northfork (W. Va.) Kroger store. That don’t matter. The bite taught me that God comes before any job.”

Chafin, a disabled coal miner, can quote almost verbatim the 16th Chapter of Mark in the Bible where it is written “and they shall pick up serpents.” He is the first this night to take a rattlesnake out of the box.

“In your name, Lord. In your name, Lord,” Chafin says over and over.

Snake-handling is outlawed in the neighboring states of Virginia and Kentucky. Services at the Jolo church have been disrupted on several occasions by drunks throwing firecrackers. This night, a West Virginia state trooper sits in the rear of the church.

“Let’s have ourselves a time,” the Rev. Elkins shouts as the lead guitarist plays “You Gotta Move.”

The snakes are usually passed around by the same 10 to 15 persons. If someone is bitten, that person is not deemed a sinner. Handling the rattlesnakes or copperheads is considered a test of faith, and the outcome of individual contact with a snake is not considered important.

Cindy Church has been attending services for several months, but has yet to pick up a snake. The 16-year-old student at nearby Iaeger High School says she “is waiting for the spirit of the Lord to give me the complete faith necessary to accept the offer of a snake. I’ll know when it’s the right time.”

She says she is the only student at her high school who belongs to a snake-handling church.

“I’ve been rebuked by a few kids, but that has made me a stronger person. Most of my classmates know how much my faith means to me, and more and more I think they understand,” she says after the service.

Cindy attended services as a child at the Jolo church with her parents and grandparents. Then came the move to Ohio, a state in which snake-handling is illegal. The family stayed a few years, but eventually moved back to West Virginia.

“We wanted to be able to express our religious convictions,” Cindy Church says.

She isn’t sure what her feelings will be when she first touches a poisonous snake.

“The power will be all over me, but I know I’ll be in control of my actions. I know I’ll feel the snake on my skin.”

She dates a young man who, while he doesn’t share her religious views, understands her feelings and sometimes even attends services with her.

“I’m lucky to have someone like that.”

At first, Cindy Church admits, “The rule against smoking was a burden to me. But I’ve adjusted, and now I wouldn’t want things any other way. I’ve accepted the fact that I am not of this world, but the next.”

Passing around the snakes in Jolo

Passing around the snakes in Jolo

Remembering The Timbering Days

1977

The once mighty lumbering town of Maben, W. Va., has been reduced to crumbling wooden company houses made soggy by the winter rain. The 18-foot logs that once thundered down to the mill pond are now mere splinters in the Slab Fork Creek bed.

The Wyoming County community was the thriving headquarters of the W.M. Ritter Company, an outfit that at one time was the largest producer of hardwood in the world, according to Georgia-Pacific, the firm that bought out Ritter’s holdings in 1960.

More than 400 men processed and loaded lumber for shipment in Ritter’s heyday in the late 1930s.

Today, the old Ritter school is deteriorating on the side of Rt. 54, and only brick from the boiler room remains of the timbering operation where lumber was once stacked as high as telephone poles.

Walter Monday of Mullens was a 20-year veteran of William McClellen Ritter’s life’s work. Monday started in Maben in the early 1920s and left during the Second World War when the operation was “all sawed out,” to use his words.

I ask him to walk the grounds with me.

“The old hotel was here,” Monday says, pointing to a muddy field beside a narrow bridge. “It burned down years ago along with the sawmill and processing camp. The company store was in the same area. When it burned, some of my work records were lost.”

When work gave out, many men landed jobs in the coal mines.

“The money wasn’t that good at Ritter at the end,” Monday says. “When I found a job underground, I earned about 50 cents more an hour.”

He explains that the chunks of lumber – mostly oak, poplar and pine – were allowed to float to the bottom of Slab Fork Creek where the wood was either processed into finished goods or shipped on rail cars.

“Sometimes Mr. Ritter would visit the docks. He was a pretty regular guy and didn’t put on airs. I guess he had a lot of money, though.”

In the early days, Monday says, Maben was a “mighty fine” company town, complete with wooden sidewalks and flower gardens.

“They say that Mr. Ritter used to tell anybody who’d listen that there was about 50 years of timbering in Wyoming County. Turns out that was about right.”

Walter Monday takes a last look at the decrepit company houses.

“I miss it, but I’m thankful I was able to work as many years as I did. There aren’t too many of us timbering men left, you know.”

Glen Looney lives across the Virginia state line in Hurley. The 78-year-old man hired on at Ritter in 1914.

“Me and the mules worked hand and hoof. You had to be a man to work for Ritter. You either did it their way or you got sent home.”

“Their way” meant putting in 10-hour shifts for 25 cents an hour in the tall timber that concentrated in the Little Prater and Knox Creek sections of Buchanan County.

“The camp was designed with self-sufficiency in mind,” Looney explains. “We had a commissary, a blacksmith and other necessities of the times. The quarters were portable. The bosses would simply drag the camp along as we proceeded further and further up in the woods.”

He grins.

“It was pretty primitive. We had a stove in the lobby, but there was no heat in the living quarters. We suffered some.”

Employees could either stay at the camp permanently, or pay 40 cents a night for boarding privileges until the weekend. Looney chose the latter.

“We worked in teams and each team was expected to produce 40 logs a day,” Looney says. “If the foreman put you in what we called ‘heavy wood,’ there was no problem getting the 40. But if the boss was mad at you, he’d put you in an area where there were fewer trees and you’d have to really sweat to get the quota. A man who didn’t help produce the 40 didn’t stick around very long.”

Looney remembers fights on almost a nightly basis.

“One time we were working up Slate Creek when this one man cut another across the temple. I’ve never seen so much blood. One wash pan would fill up and they’d bring in another one. It was nine miles to any civilization, but there was one man in the camp who had a reputation for stopping blood. Well, they called him in. I was there when he put his fingers on the man’s head and the blood stopped. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Timbering began to wind down in Buchanan County in the late 1920s.

“I probably stayed at Ritter for about eight years,” Glen Looney says. “I went to the mines and later took up carpentry work. If I put a nail in a piece of wood, it stayed.”

The days of skinning trees remain etched in his brain.

“I wouldn’t wish young people to have to work as hard as we did back then, but a small dose would be good for them. You can’t look ahead until you’ve seen the past.”

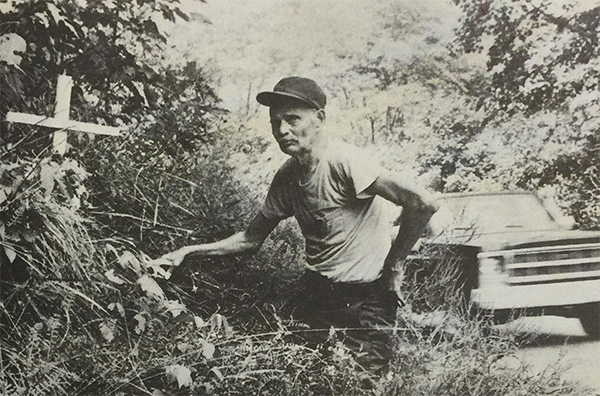

On The Prowl For Poisonous Snakes

1979

FILBERT, W. Va. – The last time Billy Reed was bitten by a snake, the doctor suggested he find another hobby, or at least another reptile.

But Reed just laughed, said “Can’t do it, buddy” and proceeded to leave the examining room for the high country around this corner of McDowell County where scores of copperheads and timber rattlers are on the crawl.

Although his wife can’t stand the creatures and most neighbors think he’s crazy, Reed is known up and down the coal camps around Gary as the man who has killed more than 200 poisonous snakes.

“It’s a hobby, buddy – just like stamp-collecting,” he says.

Reed is a mine troubleshooter for U.S. Steel, and busies himself six days a week installing mine fans or repairing pieces of heavy equipment. But come quitting time, he’s a snake man through and through.

And he’s not alone. Friends Phil Salcines and Harold Finley regularly join him in the woods about the Gary No. 9 mine.

“Some days we’ll kill more than a dozen and other days we can’t buy one,” Reed says as he pokes around a suspected den by the side of the road. “See these lines in the soil? They’re snake trails. That’s how you track ‘em. This one is cold, though. The snake done moved on.”

Reed and his pals figure they’re providing a public service by helping rid the area of poisonous snakes.

“This is good hunting ground, and the shame of it is many men are afraid to come up here because snakes are all over the place. We’ve killed a bunch, but there’s a bigger bunch left.”

There’s money in it when Reed and company vanquish a rattlesnake, as plenty of McDowell Countians are willing to shell out three bucks for the rattles.

“No bounty on the hides, though,” Reed says.

Salcines did give one rattlesnake to the Gary High School biology department, but that was a special specimen that measured a full seven inches around the belly.

“I used to give some of my catch to those snake handlers at the Jolo church, but no more,” Reed says. “Those people are a little too strange for me, and I don’t want it on my conscience if one of my snakes kills somebody.”

The handlers are fearless and that bothers Reed.

“One time I had a whole mess of snakes in a sack and brought ‘em to this guy who goes to the Jolo church. Buddy, he didn’t even think twice about sticking his hand in the bag. He must’ve charmed them snakes or something, ‘cause if I stick my hand in there them rattlers would eat me up.”

A fellow doesn’t hunt snakes as long as Reed has without learning a few things:

Reed wears no special garb. Not even a pair of gloves.

“I carry a two-pronged stick. Some guys like to step on a snake when they catch it, but the stick works best for me. Helps me pin ‘em against the ground.”

He is one stubborn man when on a hunt.

“One time I had this rattler cornered inside a hollow log, but I couldn’t get to it. I swear it was five miles or more back in the woods, but I went all the way home, got me a buck-saw and went all the way back to the log. The snake was still there, and in a couple of minutes he was all mine.”

Reed has tried snake meat, but finds its chicken-like taste not to his liking.

“I understand there’s a store or two in Princeton (W. Va.) that sells rattler meat. Maybe they’d like to hire me to make sure they keep a good supply.”

As you might expect, the guy is quite the outdoorsman. He never forgets a beaver pond or a silver maple or a petrified tree. A gun and fossil collection competes for attention in his den. And even though he works for a coal company, he’s against strip-mining because he says it ruins the pheasant and turkey hunting.

Billy Reed (CB-dubbed Tall Man because he isn’t) doesn’t add to his total this day. He leads the way out of the woods a few minutes before sundown.

“Buddy, some people tell me I ought to be scared. That’s a laugh. It don’t bother me at all to be eyeball to eyeball with a rattler ‘cause I know who’s gonna win out in the end.”

Legless Man Wants No Favors

1979

GARY, W. Va. – “I don’t want to be a part of a sad story,” Jimmy Garnick insists. “If it’s a story about me, it’s got to be happy because I’m a happy-type person.”

The 50-year-old McDowell County man turns quickly in the chair and lets his artificial legs dangle where they’ll have more room.

Garnick lost the limbs in 1951 in a mining accident that claimed the lives of four co-workers and injured 11 others. He learned to walk again, and holds down a bookkeeping job with a local lumber firm that supplies mine props to U.S. Steel.

It’s an understatement to say Garnick is a stubborn, determined and confident person.

Garnick was more than ready to enter the mines when he turned 18. His father died when he was an infant and his mother was sickly, so it was important to bring home the fattest paycheck possible.

He worked without incident at the Ream mine until the day a wall collapsed.

“That mountain bump threw me against the crib we were working on, and then a piece of machinery ran over me. I was in shock, but I stayed awake. They say I smoked a couple cigarettes while they were carrying me out. They also say it wasn’t a very pretty sight down there what with pieces of arms and legs all over the place.”

Garnick knows it was persistence that landed the bookkeeping job, not talent.

“When I hired on, I probably hadn’t written three checks in my life. I’m a good learner.”

The man still has his original wheelchair, but he’s gone through six sets of limbs.

“If I gain or lose a lot of weight, my legs are awful uncomfortable. Now that I’ve slowed down my eating I need a smaller pair.”

He reckons he would be a coal miner today if he not for the accident.

“Of course I would have fought the Korean War first. I remember I got a big laugh in the hospital when the government mailed my draft notice.”

Garnick still deals with the after-shocks of the tragedy.

“Every Tuesday for the last 14 months I’ve driven to Beckley (W. Va.) to get my teeth worked on. The jolt knocked them loose and the bottom set got crooked. Doctor says I have big chunks of bone missing from my jaw. He says it might take a year before everything gets right.”

Garnick keeps his two canes behind the desk at work.

“Some of the men probably don’t even know about my little leg problem. That’s the way I like it. I don’t want to be any different from anybody else.”

Black Players Recall Coal Camp Baseball Games

1981

The fences were wooden. The bats were borrowed. The scores were forgotten.

And the faces were black.

The New River Giants and the Raleigh Clippers started playing baseball during the Depression. The teams flourished during the pre-union days because the coal companies were more than willing to buy a few gloves and bats to keep their miners/players from complaining about conditions underground.

The end came when the United Mine Workers forced an increase in wages, an action that resulted in the bulldozing of most of the company-owned playing fields.

Nathaniel Smith of Beckley, W. Va., played for both teams. He was a power-hitting shortstop considered by some to have been Major League caliber. But the closest he ever came to the top was an unsuccessful tryout with the Kansas City Monarchs, one of the top black barnstorming teams in the nation.

The color of his skin worked against Smith as his diamond heyday was well before Jackie Robinson broke the racial barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

“You can’t go after a job (the tryout with Kansas City) when you’re 31 years old,” Smith says. “That’s the time to be coming out of the game, not going into it.”

He suited up when he was 15, the first year he worked in the mines. He dug coal for 30 years and played for the Clippers until the late 1950s.

“We’d work the mines five days a week, and practice twice a week from quitting time at 4 o’clock until dark. The games were on Saturdays and Sundays, and they’d usually be against semipro teams from Cincinnati and Louisville and places like that.

“I was lucky enough to get a good job running a motor in high coal. I knew the superintendent real well and he took care of me. I don’t think I could’ve played as long as I did if I worked the low coal.”

The companies knew the games were good for camp morale, so they hired quality players whenever they could. If a man could run, hit and field, he rarely had trouble finding work. In fact, promotions often had more to do with performance on the field.

Recreational opportunities were scarce in the camps, so the weekend games were the highlight of the social calendar.

“The coming of the union changed a lot of feelings and the companies no longer subsidized us,” Smith says. “The ball diamonds got torn down, including the one the Clippers used. There used to be a field every two or three miles in the coalfields, but now you can’t find one to save your life.”

The Clippers had to scramble to find a place to play. Players pooled their money and built a few wooden bleachers on an empty lot, but the crowds stayed away.

“You can’t charge if you don’t have a nice stadium,” Smith says. “Besides, by that time more and more people were getting cars and leaving the camps, so that meant they had other things to do than watch us hit baseballs.”

He says there never was any racial trouble to speak of.

“Not unless you count the time we went to Clinchco (Virginia). There weren’t very many blacks down there, and a few drunks started giving us a hard time when we got way ahead. But the sponsors of the other team saw to it nobody caused trouble.”

Smith will never forget the two games he played with the legendary Satchell Paige.

“We hired him to pitch for us against the Homestead Grays. He always brought a crowd, so we booked the exhibition game in Charleston (W. Va.). Satchell got almost all the money, but we agreed on that to get him to come.

“The biggest trouble we had with the man was getting him to the games. He was a celebrity and would do radio interviews until right before the game. We barely got him to the park in time to get warmed up.

“We lost the two games, but we didn’t have anything to be ashamed of. The Grays had a guy named Josh Gibson who might’ve been the greatest catcher to ever play the game. We played before something like 5,000 fans and it was great.”

Nathan Payne of Rhodell came to Southern West Virginia from his native Alabama. The first baseball fields set aside for his race were pastures that the players had to tame with mowing scythes.

The black athletes were a ragtag, poorly organized bunch who knew all too well that, despite their natural abilities, there would be precious little recognition for their talents and little chance to play beyond the shadows of the coal tipples.

Payne helped change that. After the dust from the Raleigh County man’s sphere of influence had settled, dozens of coal camp baseball players of both races received opportunities to play organized ball.

First and foremost, Nathan Payne was a coal miner. He picked slate when he was 15 in the early days of a mining career that lasted 53 years.

“Anything I did with baseball came after I got off the cutting machine. I knew the priorities as well as the next man.”

Payne was a hotshot infielder as a youngster and was playing on a men’s traveling team at age 13.

“Baseball helped me get out of a lot of chores back home in Alabama. I was always ready to go anywhere for a game, and I promised my dad faithfully I wouldn’t get into any meanness. There was something about the running and throwing aspects of baseball that always fascinated me.”

Payne played some after his father moved to Wyoming County – wages were almost three dollars a day higher in West Virginia – but as the years passed he became more and more interested in organizing and overseeing coal camp teams.

“Occasionally it wasn’t just about baseball. Moonshine would get changed hands and the stuff sometimes got as far as the team bench. There was more than one guy on the club that I had to bail out of jail for being drunk.”

Guarantees for games ranged between $100 and $150. Payment wasn’t a certainty.

“I remember one time we went to Logan County (W. Va.) and the manager of the other team tried to stiff me out of our money. I heard he was hanging out at the local American Legion hall so I took my catcher with me – he was mean and as big as a truck – up to where the man was. I threatened to confiscate all his equipment if he wouldn’t pay up. We almost had a fight, but we got our money.”

Payne continued to work on his cutting machine, but gradually broadened his base as far as baseball was concerned.

“I had seen coal camp players come and go for years and I knew there was some big-league potential. The problem was they didn’t have any way to draw attention to themselves. I became a talent scout and worked this end of the coalfields for professional teams.”

None of his prospects cracked the majors.

“Some of the men I signed kinda got swayed by the lights of the big city. Others got homesick and a few got in trouble. I guess it just wasn’t meant to be.”

Scouting wasn’t a lucrative proposition for Nathan Payne.

“I was always pretty informal about the whole thing. They never could get me to itemize expenses and things like that. Really I did it (keeping an eye on the players) because I enjoyed it.”

He looks back fondly on the coal camp games.

“Baseball was relaxation. Sometimes we’d play three games a day and it didn’t have to be all sun-shiny like it does today. Baseball was good clean fun back then and it meant a lot to all of us involved. After a day of working underground, playing ball was kinda like being free.”

He Knew Some Hatfields And McCoys

1979

DANIELS, W. Va. – William Saunders is proud of two things in his life that has extended several months past his 90th birthday.

One is the doctor, who recently said he needs no pills and that he’s in good shape for “an old critter.”

And the Raleigh County man is glad he never got in a fracas with the Hatfields and McCoys, who were fussing and feuding when he was growing up along the Big Sandy River in Wayne County.

Saunders’ grandfather was a Hatfield, so the white-haired man knows more than a little about the famous feud between the two armed camps on both sides of the river that separates Kentucky from the Mountain State.

“I knew most of the Hatfield boys – Willis, Doc, Johnse and the rest,” Saunders says. “They were all mean as could be, but they didn’t have anything on those Kentucky McCoys.”

He says there was a store in the Prichard section of Wayne County where the Hatfields gathered when they weren’t gunning down McCoys.

“I reckon I traded at that place a thousand times or more when I was a youngster. I’d just sit around all day long and listen to all the talk. I didn’t mention it at the time, but I never saw how anybody could get any joy out of shooting innocent people just because you didn’t like their last name.”

When 1907 rolled around, Saunders was positive he didn’t want to live the rest of his days by the Big Sandy. But he wasn’t sure on just how to go about leaving home.

“So I sneaked out one night when the moon was low. I was with a couple friends and none of us knew exactly where we were going. We got as far as Kenova (W. Va.) where we all got jobs digging sewer pipe.”

He didn’t mind the digging part of the job, but after three weeks the 18-year-old Saunders got mighty tired of sewer pipe.

“That was when I decided to go into the mines. I started out hand-loading and before long I was digging 40 tons a day when we were in high coal. I didn’t turn over the keys to my tool box until I had been underground 42 years.”

Saunders only finished seven years of his McGuffey Reader, but says his lack of education didn’t hold him back.

“Lots of times they made me boss when I never had the classes for it. They just asked me not to tell anybody.”

He hasn’t forgotten his boyhood days when gunfire and threats of gunfire were all around.

“I don’t care what anybody says. The Hatfield-McCoy feud started when a McCoy stole a pig that belonged to a Hatfield. Forget all that talk about the love affair (between Roseann McCoy and Johnse Hatfield). When I was a little boy, I asked straight out what started the whole mess and my grandmother said it was over a pig that was worth around 50 cents. And she ought to know because she was a Hatfield.”

The feud began in 1865 and bad feelings continued into the 20th century. Ten family members lost their lives.

“A lot of people don’t know it, but there were many battle royals going on in that area around the coming of the 1900s,” Saunders says. “There were a lot of mean families who went at each other with their long rifles. The Hatfields and McCoys were just two of them.”

William Saunders was too busy working to get involved in the long-running dispute.

“That would have been good advice for the two families to take. I think one reason there were so many killings was that neither family much believed in breaking a sweat.”

Has history over-dramatized the mountain feud?

“Nope, because it really happened. People really lost their lives and everybody along the river stayed scared a lot of the time. I’m not sorry I left.”

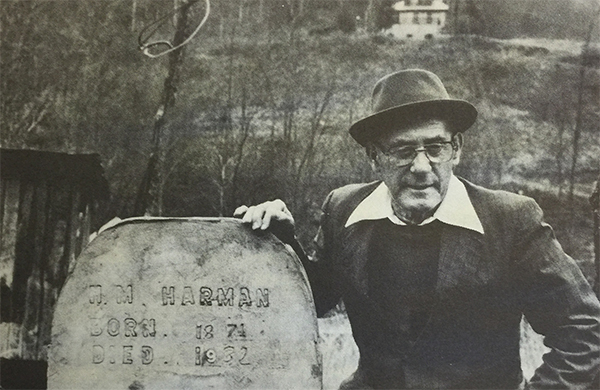

His Markers “Not As Slick’ And Not As Pricey

1979

JOLO, W. Va. – Earl Rife was walking through a rural cemetery when he noticed that many plots lacked tombstones.

This got the former coal miner to thinking.

“I figured the families couldn’t afford those expensive $200 jobs that the funeral homes charge, so they decided not to have a stone at all,” the 71-year-old Rife says. “Well, I was a pretty good carpenter in my time, so I came up with the idea of making homemade tombstones. That was 11 years ago when the doctor took me out of the mines on account of black lung. I reckon I’ve made 400 or so since then.”

The McDowell County man mixes his own cement and, depending on the size of the desired tombstone, pours the works into one of two wooden molds. Exactly two and one-half hours later, Rife gets out the plastic letters that came from Hong Kong and makes imprints in the still-wet cement.

The upshot is birth and death date in letters that are more or less straight, and in spelling that’s more or less correct.

“My tombstones look like the kind they had back in the Civil War – you know, with the little letters running all over the rock,” Rife says as he shows off a couple of 100-pound demonstrator stones that sit outside his mountaintop dwelling. “Tombstones are real important to people around here. Mine might not be as slick as those you’d get from a funeral home, but the quality is still there, believe you me.”

When we spoke, he was charging $35 for a smaller model and $60 for a full-sized stone.

“The way I look at it, I’m saving a little history. There used to be a lot of homemade tombstone guys in this corner of the state, but I’m the only person I know who’s still going.”

It takes about a day for Rife to turn out a marker. These are careful hours because there is product risk involved.

If he waits too long, it can be almost impossible to remove the footer from the concrete. If he doesn’t wait long enough, the stone can crack.

“I keep on working until I get it right,” Rife says as he shows how sometimes the letters can slip on the cement and cause a name or a death date to be out of line.

“The only thing I don’t do is deliver. I’m not about to lift one of these babies.”

The man is not limited to traditionally shaped tombstones.

“I’ve done a few with crosses on top, and once I put a picture of the man and his wife on the stone. All I had to work with was an old tinplate picture, but it didn’t turn out too bad.”

So far, Earl Rife has not been asked to put any poetry on any of his stones, but he says he could handle the request.

“I’d just have to squeeze the space a little more, that’s all.”

While he hasn’t purchased a fancy cash register or anything like that, he has toughened his pricing policy.

“Unless I know a person, I get half my money up front. I ended up making three headstones for free for this one man and I learned my lesson. I may be a small-timer, but I wasn’t born yesterday.”

Earl Rife with one of his creations

Earl Rife with one of his creations

Early UMW Organizer Hasn’t Forgiven

1978

LECKIE, W. Va. – Clyde McGraw is one of the few original United Mine Workers organizers still drawing breath in McDowell County. The departed can take solace in the fact that the white-haired man has more than enough venom in his heart to compensate for the declining numbers of his organizing mates.

Venom against the Taft-Hartley law, against Baldwin-Felts detectives, against non-union coal mines, against payment differentials in the 1950 and 1974 union retirement program and, last, venom against what he calls “unfeeling, uncaring coal companies.

“The fighting fever has been boiling up inside me all my life and I can’t get shed of it,” he says.

McGraw’s staunch UMW feelings are hand-me-downs from his activist miner father, who worked in what his son says were more than 100 different mines from Alabama to Pennsylvania.

“Dad was fired from more jobs than I can remember. He wasn’t content when things weren’t right.”

Clyde McGraw first worked in the mines in 1913 when he and his brother loaded coal that had been dynamited by their father. It was the start of a career underground that didn’t end until 1972.

“I started organizing coal mines in the middle part of West Virginia in 1922,” he recalls. “There wasn’t any organizing in the Bluefield coalfields to speak of until 1933.”

Some recollections:

-- “It took us until the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor to organize the U.S. Steel operations in Gary. The miners there were unable to look past the short run of things. They couldn’t see that we were actually there to help them…

-- “I always carried a gun when I was out organizing. Sometimes I didn’t need it, but sometimes I did…

-- “I never was paid a dime for my organizing work. A man doesn’t have to get paid money if he is doing something he loves…

-- “We had to get 51 percent of the men at a mine to sign UMW cards before we could force an election. Our work was made harder because we couldn’t approach a miner on company property. Usually we would get several sympathetic fellas to mill around a man who was signing our card, so the company couldn’t tell who was the latest man to start thinking union…

-- “Jenkinjones in McDowell County was one of the toughest mines to organize. There was no road up there, only a train. If a miner who lived up that hollow owed even so much as a dollar on food or furniture, then that food and furniture would rest at the bottom of the hollow until the debt was paid in full. That kind of company attitude made it real hard on us…

-- “I remember trying to organize men living in shanties where the only running water was from holes in the roof. At that time, the coal company had the right to make a man move lock, stock and barrel on just three days’ notice. Later we were able to change that rule to require 30 days and then 60 days of advance warning…

-- “We were usually working no more than two or three days a week during the organizing years. I hit the road with my sign-up sheets on about all the days I didn’t work and on most of the days after I put in my shift…

-- “My family never went hungry even though I was fired from many mines on account of the organizing. Even when I worked in muddy punch mines, I always had food for my family. I was smart. I cleared me out a garden way up in the hollow, and after work I’d carry down a sack plumb full of all the vegetables we would need to eat that night.”

Clyde McGraw says he would be equally unbending toward coal companies if he had his life to live over.

“The only time I’d change was the few months I went to Baltimore to help organize a cork operation. We had us a merry old time in the big city, but I’m sorry about the time I spent away from the mines.”

As he speaks, a coal train rumbles past the side of the mountain. Its roar gives McGraw time to sum up his case.

“A man is just flesh and bones and he’ll die. But not the union in a man. That’s something special and it lives on after the man is gone.”

Old Pete Finally Earns Citizenship

1980

NORTHFORK, W. Va. – There’s a lot of Jimmy Cagney in Pete Falcamanto.

Same squat appearance. Same pugnaciousness. Same stubbornness. Add to that the distinct facial resemblance, and it’s no wonder he gets kidded about being a ringer for the famous gangster actor.

But there is an important difference. Cagney never had to fight more than 40 years to earn his citizenship.

“Being in the Second World War and getting shot up wasn’t near as much trouble as getting my papers,” the McDowell County man says. “A lesser man would have given up.”

But that wouldn’t be Falcamanto’s style.

He was one of 10 persons to become U.S. citizens the other day during a ceremony in Bluefield’s District Court.

No doubt it wasn’t easy for the other nine new Americans to meet the qualifications. And they probably stood just as stiff and proud as the 70-year-old Falcamanto.

But that’s where the similarity ends.

He came to this country from Italy when he was 2 years old. He worked 38 years in the coal mines, picked a few lemons in California during slack times, participated in the D-Day invasion and earned a Purple Heart for his troubles.

All in all, a significant enough contribution to the American way of life to earn a man his citizenship, Falcamanto figured.

Not so, the government said.

“Most times they turned me down because I couldn’t pass the test. I can write my name and I don’t have any trouble with highway signs, but that’s about as far as I can go with education.”

Falcamanto can’t remember how many times he’s tried to get his papers.

“Each time elections came around my memory would get refreshed and I’d start the ball rolling again. I’d drive all over the place trying to get myself approved, but nothing worked out. I got fingerprinted more often than a common criminal.

“One time the girl at the test center asked me to spell a word. Boy, did I get mad. Another time, they wanted me to take a special course at Marshall University. I told them that was asking me to take a pretty big step – going from first grade to college.

“I kept telling the registration people I served my country overseas and supported my family with a good job. I wanted to be a real American like everybody else.”

Finally, it was decided Falcamanto fit a special category of unnaturalized citizens who had been living in the United States for 25 years. A letter or two from his congressman later, Falcamanto was told he had finally been accepted into the fraternity of citizens.

“If they hadn’t put me in, I was gonna write a letter to President Carter. I was gonna tell him I fought in artillery with General Patton and that I almost got my leg shot off. I wasn’t the greatest of soldiers. I was afraid I wasn’t gonna get out of Germany alive. I could’ve been a corporal, but they were the gunners and too many of them were getting killed to suit me.”

Falcamanto retired from the mines in 1969.

“I worked with a lot of mules, and I still have the kick scars on my stomach to prove it. But life’s been good. I don’t have any regrets about anything other than schooling. I did more rock-throwing than studying and that held me back.”

Many family members still live in Italy.

“I know I’ll never see them again. That’s all right. I’m where I want to be.”

The Miners’ Man Inside The Scale House

1976

GHENT, W. Va. – From 1939 until 1953, Earl Mills was the miners’ representative inside the scale house.

“I was a checkweighman,” the Raleigh County man says proudly. “It was my place to guarantee that the underground hand loaders were paid fairly, and to make sure the coal company didn’t take advantage of them.”

Mills worked at the Stephenson operation in Wyoming County not long after the United Mine Workers’ initial efforts to organize in the area. There was much wariness between the company and the UMW concerning the amount of coal the miners were getting credit for since they were paid by the ton.

It was Mills’ job to make sure the loading figures were accurate, and to balance them with a company man who was his shift-mate inside the scale house.

“I started out as a hand loader at Stephenson. The men were pretty disgusted with the previous checkweighman and they kept getting on me to take the job. I said I’d take it on trial. That trial lasted 14 years and I was never opposed in seven elections.”

Mills and his company companion knew the tare (empty) weight of the cars. The hand loaders’ tags were on the side, and the job required them to record the total tonnage (on tightly rolled white paper like that used in adding machines) as well as each miner’s individual efforts.

“I didn’t have any trouble with the first company man,” Mills says. “He was as honest as could be. But that second one was a different case. He would try to cheat the diggers whenever he could and I had to watch him like a hawk. We had several run-ins and I carried a pistol to work.”

At the end of the day, Mills would take his figures to the miners while the other set of totals became part of company records.

In 1939, Mills earned $9.75 a day, a little less than the average hand loader.

Before the age of checkweighmen and scale houses, there were dock bosses who supervised the coal-loading.

“They were paid by their ‘docks’ or when they would cut a man’s pay when they felt the coal cars weren’t loaded to the brim. You had to have a graveyard hump before the dock boss would consider it full.”

Loading “bone,” or non-coal material, was always a problem, Mills says.

“Rules at the time permitted 500 pounds of bone in a car but no more. Shovel more than that the first time and you got a warning. Do it a second time and you got laid off for two days. The third time you were fired.”

Mills says the hardest thing for the union to accomplish was convincing the coal operators to accept scales to weigh hand-loaded coal. He remembers one operation where the miners were being paid for loading what they thought were two-ton buggies. The conveyances were determined to hold closer to three tons and the men’s pay jumped almost a dollar per car.

“One superintendent said he would die first before he permitted scales at his mine. The night after we weighed the first coal there, he committed suicide in his living room.”

Earl Mills worked 42 years in the mines, beginning in 1918 when the coal was hauled by mules. His checkweighman job ended in 1953 when mine mechanization was completed at the Stephenson operation and tonnage verifiers were no longer needed. The mine had gradually cut down on the number of hand loaders since the late 1940s as more and more machinery was used.

“It was tough being a checkweighman. The diggers desperately needed someone they could trust in the scale house because their paychecks were on the line. Increased pay to the inside men was money out of the coal operators’ pocket and they would apply pressure the other way.

“You had to be mind-strong to hold the job. That’s something I believe I was.”

The Voice Of Uncle Remus Is Silenced

1979

TALCOTT, W. Va. – A stroke has dealt a cruel blow to Uncle Remus and all his animal friends.

Over the years, Icie Sweeney has become well known around this corner of Summers County for her rendition of Joel Chandler Harris’ stories about Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, the Tar Baby and, of course, that plot of ground known as the Briar Patch.

The 83-year-old storyteller knows just when to bring her hands to her face to elicit the proper amount of fear from her audience, and exactly when to cackle uproariously to inject comedic relief.

The lady first heard the tales 75 years ago from her aunt, a former slave who was not permitted to learn to read or write. The attentive little girl became the conduit that enabled the Uncle Remus stories to reach yet another generation.

The gentle black woman has told the tales on porches, on playgrounds and in classrooms. She was even invited to go to Charleston, W. Va., and share her art with an assembled multitude at the Cultural Center.

Then came the illness that has at least temporarily silenced her characters.

“It’s called nerve paralysis and it’s hit on both sides of my body,” she explains. “I’m supposed to get better inside of a year, and believe me when I say I’m looking forward to that day.”

While she can still be understood, the stroke has robbed this storyteller of her greatest gift – a sparkling diction that has captivated many a youngster over the years.

“Mama used to tell old stories before bedtime and they seemed to always bring us such sweet dreams,” says Nellie Patterson, one of Sweeney’s five children and her caregiver.

“They called our part of Talcott Pie Town,” Icie Sweeney says. “That’s because my mother-in-law stayed busy making sweets for all the railroad men who worked on the Big Bend Tunnel.”

A statue of John Henry – the legendary steel-driving man – is a mile from Sweeney’s house.